- Author: Joe Stewart and James Bettke, SecureWorks® Counter Threat Unit™ Threat Intelligence

Summary

"Nigerian prince" and "419" scams have plagued victims for decades and transitioned to the Internet in the 1990s. There are many variations and names for these scams, which originated in Nigeria. The scammers refer to their trade using the terms "yahoo yahoo" or "G-work," calling themselves "yahoo-yahoo boys," "yahoo boiz," or "G-boys." However, the simple con man fraud practiced by many West African-based threat actors is being replaced by a new crime they refer to as "wire-wire," "waya-waya," or "the new G-work." These terms have not entered the mainstream lexicon as of this publication and are not well-defined, but SecureWorks® Counter Threat Unit™ (CTU) research indicates that they refer to the evolution of low-level con games into more sophisticated and conventional cybercrime that is compromising businesses around the world. The businesses range in size and span industries from machinery manufacturers to countertop material manufacturers to chemical companies. The cybercriminals use spearphishing and malware to gain direct access to organizations' computers to facilitate the theft of large sums of money without the victim's knowledge.

A Facebook search for "wire-wire" reveals numerous groups and users operating in the open. They advertise their services or offer training courses about wire-wire to would-be criminals. Multiple social media platforms have a wealth of information about individual threat actors, but meticulous research is necessary to understand how these thefts are being accomplished.

Business email compromise

The Internet security industry has been aware of the evolution of largely African-based threat actors for several years. Security companies such as Trend Micro, ThreatConnect, Palo Alto, and FireEye have detailed the rise of this activity. However, awareness about how these threat actors operate and how to spot their intrusions is still low among security professionals and the public. Because these actors operate differently than other cybercriminals, it is essential to understand how they conduct their schemes. Although some wire-wire activity is simple low-level credit card fraud, the largest threat to organizations is business email compromise. CTU™ researchers use the following terms to distinguish between wire-wire fraud types:

- Business email compromise (BEC) — Hijacking an email account or an email server to intercept business transactions and redirect payments

- Business email spoofing (BES) — Sending spoofed email from an external account pretending to be a company executive authorizing an irregular payment transaction

CTU researchers have encountered many reports that use "BEC" to refer to activities better categorized as "BES." BEC is much more devious and harder to detect than BES. If these terms are used interchangeably, a potential victim may assume that verifying requests with the named executive using established communication channels will sufficiently mitigate the threat. However, this defense cannot prevent BEC fraud.

How BEC works

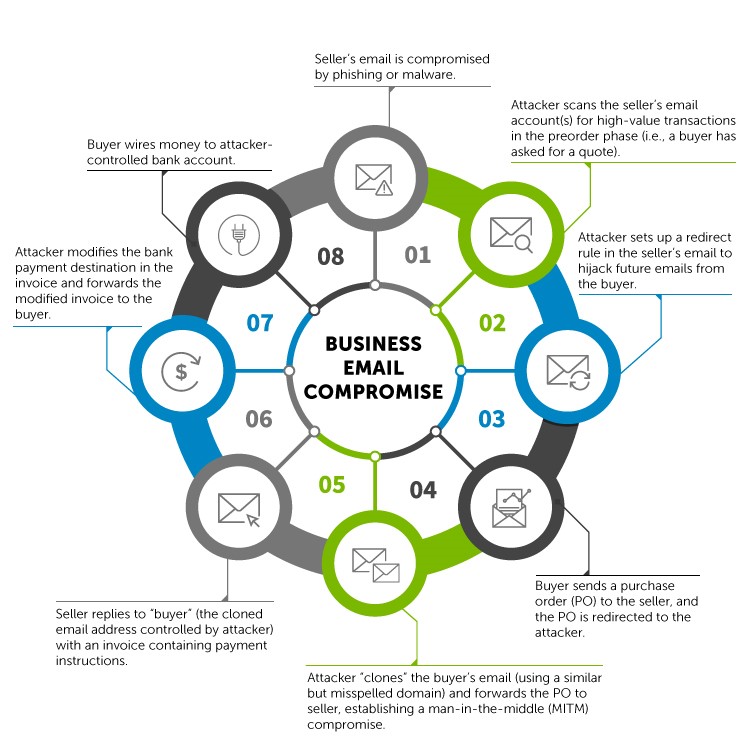

In BEC, an attacker compromises a seller's email account to position himself as a "man-in-the-middle" between the seller and a buyer in existing business transactions. The threat actor then uses his control of the seller's account to passively monitor the transaction. When it is time for payment details to be relayed to the buyer via an invoice, the threat actor intercepts the seller's email and changes the destination bank account for the buyer's payment. If the payment account does not appear to be suspicious, the buyer will likely submit the payment to the attacker's account.

To completely and transparently control the communication between the buyer and seller, the attacker must be able to control and monitor the email chain between the two parties. The first step is to compromise a business's email account, which can be accomplished easily and inexpensively with various phishing kits and commodity malware. For approximately $30, a threat actor can send a large quantity of emails containing malicious attachments (referred to as "bombing") to a list of email addresses scraped from the target's web pages. Even if only a few recipients are compromised, the potential payoff for the attacker could be thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars per email campaign. BECs follow a typical chain of events (see Figure 1), which may vary based on the details of the transaction.

Figure 1. Typical BEC process. (Source: SecureWorks)

From the seller's point of view, the transaction appears to be normal until the buyer does not pay for the invoiced goods. The only suspicious aspect the seller might detect is the change of email address between the request for a quote and the PO. The buyer will not notice a problem until the seller fails to ship the purchased goods. The seller's email address does not change because the attacker controls that email account. If the threat actor is skilled at document forgery and generates a seemingly legitimate invoice, the buyer will likely believe that the seller cheated them.

Not all wire-wire attackers are skilled. Many struggle to understand how their malware operates and how it is detected by antivirus software. CTU researchers have observed clumsily modified invoices, with payment details in a font that does not match the rest of the document and a bank account that is associated with an unrelated business name and is located in a different country than the seller. Regardless, BEC is effective against many targeted businesses.

Case study

When researching wire-wire activity, CTU researchers discovered that one of the most notable cyberheists had been executed by a Nigerian wire-wire group against an Indian chemical company and its U.S. customer. The customer, also a chemical company, sought to purchase a large quantity of chemicals from the Indian company. CTU researchers found that the wire-wire group had hijacked the email username and password of an employee at the Indian company. The company used a webmail application for its corporate email, and the employee login required only a username and password. Because employees did not have to provide another form of verification, the threat actors used the credentials to access and read the employee's emails.

The attackers identified an opportunity when the U.S. company sent a price quote request to purchase $400,000 in chemicals from the Indian company. The threat actors added a rule to the employee's email to redirect all future email from the U.S. company to the attacker's email account. The attackers intercepted the U.S. company's purchase order and resent it from another email address that closely resembled the submitter's actual email address. At this point, the attackers established their MITM position between the buyer and the seller.

The Indian company eventually sent an invoice that contained wire payment details. Because the invoice was sent to the attacker-generated email address, the threat actors modified the following information before forwarding it to the legitimate recipient at the U.S. company:

- The bank account number or International Bank Account Number (IBAN) for the attacker-controlled account

- The full name and address of the bank where the attackers' account was located

- The SWIFT/BIC code of the attackers' bank

The U.S. chemical company unknowingly wired $400,000 into the attacker-controlled account. The threat actors then laundered the money through multiple accounts in different countries, making recovery impossible and the money trail difficult to trace.

Wire-wire group profile

While investigating BEC, CTU researchers discovered a threat actor infecting his own system with malware and uploading screenshots and keystroke logs to an open directory on a web server. This misstep by the threat actors has become common and provides intelligence for some investigations into BEC activity. This cybercriminal was the key figure in a wire-wire group with more than 30 members. The information from his computer led to a valuable cache of information about the operations and identities of what CTU researchers refer to as "Wire-Wire Group 1" (WWG1) or Threat Group-2798 (TG-2798).

WWG1 operations

From an operational standpoint, WWG1's fraud activity is similar to other West African threat actors. It uses well-known commodity remote access trojans (RATs) and public webmail services to accomplish its goals. Members do not have a sophisticated understanding of malware, but the key figure in this group, named "Mr. X," provides the technical support and infrastructure that allows the group to function successfully.

WWG1 is loosely structured and does not have the conventional top-down hierarchy that is typical of organized crime groups. Instead, members pay Mr. X for his services and training by reimbursing him for expenses and providing a percentage of their ill-gotten gains. Most WWG1 group members reside in the same geographical area of Nigeria and know each other personally or are at least Facebook friends.

WWG1 social context

There are several differences between the conventional profile of a typical West African threat actor and the characteristics of WWG1 members. For example, the following attributes are often associated with "yahoo-yahoo boys":

- College-age to late twenties

- Huddle in cybercafes all day scamming victims

- Spend extravagantly and show cash and fancy cars on social media

- Resort to "juju" (voodoo) charms to improve their success (i.e., Yahoo Plus)

WWG1 members have a nearly opposite profile:

- Late twenties to forties

- Operate from home using their personal Internet connection

- Appear wealthy on social media but never display cash or fancy cars

- Are typically devoutly religious and active in mainstream churches

Social media intelligence indicates that WWG1 members are often family men that are well-respected and admired. They feel obligated to uplift other members of their community, but that usually means introducing others to the wire-wire scheme given the lack of opportunities for legitimate employment.

By examining invoices, purchase orders, and messages between the threat actors, CTU researchers estimate that WWG1 members steal approximately $3 million per year from businesses. Business losses may be as high as $6 million due to the percentage taken by intermediary money launderers. CTU researchers observed fraudulent invoices for amounts from $5,000 to $250,000, although the average amount taken from a single business fraud appears to be between $30,000 and $60,000.

Mitigating BEC

CTU researchers expect wire-wire activity to increase exponentially because this type of fraud is significantly more profitable than the Nigerian prince and 419 scams, and because individual threat actors that become proficient at this type of fraud will likely pass that knowledge to others. Vendors and other experts could take actions to mitigate BEC at multiple stages of attempted fraud.

Antivirus vendors

By rapidly detect emerging malware packed by crypter programs, antivirus (AV) vendors could impede the threat actors' activity. Crypters are software tools sold on the hacker underground that repackage malware so that it evades AV detection rules. Groups such as WWG1 depend on crypters and are frustrated when their crypter becomes well-detected by multiple AV engines. The time that the threat actors expend attempting to find a fully undetectable crypter is time they are not stealing money from victims.

International payment system vendors

Global payment system vendors such as the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) and Western Union could stop some wire transfers by providing a mechanism for organizations and independent security researchers to report money mule accounts used to launder funds in BEC transactions. If the vendors froze the accounts while conducting a thorough investigation, the threat actors could not access their bank accounts and stolen funds.

Another option may be for organizations to implement third-party "do-not-pay" blacklists for mule bank accounts, similar to anti-spam domain blacklists. This countermeasure could protect accounting departments that subscribe to such lists if the information is regularly updated. Identifying money mule accounts may require insight into fraud operations and is less-automatable than filtering spam.

Hosting providers/webmail application vendors

Vendors should implement two-factor authentication (2FA) to secure control panels and webmail installations. In June 2016, the popular cPanel control panel added 2FA as an option for its webhosting platforms. Although the three top webmail applications do not natively support 2FA as of this publication, it is possible to add 2FA as a plugin in the RoundCube webmail application. Unfortunately, many cPanel installations include multiple webmail applications, so an attacker can choose one that does not support 2FA.

Webmail vendors could also implement alert mechanisms such as "The Day Old Bread List" DNS-based real-time blackhole list (DNSRBL). This feature would help expose emails that are purportedly from buyers who have been in business for years but that originate from a domain registered a few days prior to the email being sent. Use of a new domain might indicate that the seller's email is compromised.

Public-private partnerships

The CTU research team recommends that organizations consider joining the non-profit National Cyber-Forensics & Training Alliance (NCFTA). The NCFTA works with individuals across industry and academia to identify and mitigate cyber threats. The NCFTA's Cyber Financial Program (CyFin) focuses on threats to the financial vertical.

Legal action could have a major impact on BEC worldwide. Law enforcement organizations investigating BEC should collaborate with the private security research community, especially in Nigeria, Ghana, Malaysia, South Africa, and Dubai. A collective worldwide law enforcement effort could make BEC too risky for would-be thieves.

Recommendations

Organizations can reduce their risk of BEC:

- Implement 2FA for corporate and personal email. Small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) are popular targets for wire-wire groups because SMBs typically have little or no budget for security tools beyond AV. SMBs also tend to use the least-expensive option for hosting websites and email, which is usually a cloud hosting provider. Most threat actors rely on easy access to a company's email via a commodity webmail program, so 2FA would deter all but the most sophisticated attackers.

- Inspect the corporate email control panel for suspicious redirect rules. An unexplained redirect rule that sends incoming email from specific addresses to third-party systems could indicate compromise and should trigger an organization's incident response process.

- Carefully review wire transfer information in suppliers' email requests to identify any suspicious details.

- Always confirm wire transfer instructions with designated suppliers using a previously established non-email mode of communication, such as a fax number or phone number. Establish this communication channel using a method other than email.

- Require multiple approvals for wire transfers, and ensure this procedure is difficult for cybercriminals to discover.

- Question any changes to typical business practices and designated wire transfer activity (e.g., a business contact suddenly asking to be contacted via their personal email address or a change to an organization's designated bank account information).

- Be suspicious of pressure to take action quickly and of promises to apply large price discounts on future orders if payment is made immediately.

- Thoroughly check email addresses for accuracy and watch for small changes that mimic legitimate addresses, such as the addition, removal, substitution, or duplication of single characters in the address or hostname (e.g., [email protected] versus [email protected], or [email protected] versus username@ examp1e.com).

- For organizations that use intrusion detection and intrusion prevention systems (IDS/IPS), create rules that flag emails with extensions that are similar to company email extensions (e.g., abc_company versus abc-company).

- Limit the information that employees post to social media and to the company website, especially information about job duties and descriptions, management hierarchy, and out-of-office details.

- Consider adopting the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) standards to deter money laundering and fraudulent wire transfers.

- Consider using the free pdfxpose tool that CTU researchers developed to help detect wire-wire fraud. CTU analysis of WWG1 activity revealed that the threat actors edited PDF invoice files by redacting the original payment details with a white opaque rectangle and then overlaying it with the money mule account information. This tool searches for sub-page-sized opaque rectangles with text overlays and adjusts the opacity and color to reveal potentially suspicious edits.

Conclusion

Since 2012, wire-wire activity has been targeting businesses around the world, and its potential profitability lures a growing number of threat actors. The monetary losses to victims can be significant, and the activity is often not detected until the money has been stolen and laundered through various channels. However, organizations can take actions to minimize their risk to this type of BEC, and collaboration among organizations, vendors, and law enforcement could complicate the process and reduce the appeal for potential attackers.

References

cPanel documentation. "Two-Factor Authentication." June 29, 2016. https://documentation.cpanel.net/display/ALD/Two-Factor+Authentication

Flores, Ryan and Remorin, Lord. "Piercing the HawkEye: Nigerian Cybercriminals Use a Simple Keylogger to Prey on SMBs Worldwide." Trend Micro. June 19, 2015. http://www.trendmicro.com/cloud-content/us/pdfs/security-intelligence/white-papers/wp-piercing-hawkeye.pdf

Giles, Jim. "One Per Cent: Meet the Yahoo Boys: Nigeria's email scammers exposed." New Scientist. February 13, 2012.

Hernandez, Erye; Regaldo, Daniel; and Villeneuve, Nart. "An Inside Look into the World of Nigerian Scammers" FireEye Labs. July 20, 2015. https://www2.fireeye.com/rs/848-DID-242/images/rpt_nigerian-scammers.pdf

Krebs, Brian. "Spy Service Exposes Nigerian 'Yahoo Boys'." Krebs on Security. September 9, 2013. http://krebsonsecurity.com/2013/09/spy-service-exposes-nigerian-yahoo-boys/

Palo Alto Networks. "419 Evolution." July 17, 2014. https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/apps/pan/public/downloadResource?pagePath=/content/pan/en_US/resources/research/419evolution

Support Intelligence. "The Day Old Bread List." http://support-intelligence.com/dob/

ThreatConnect Research Team. "Adversary Intelligence: Getting Behind the Keyboard." May 31, 2015. https://www.threatconnect.com/adversary-intelligence-behind-the-keyboard/

Secureworks has been acquired by Sophos. To view all new blogs, including those on threat intelligence from the Counter Threat Unit, visit: https://news.sophos.com/en-us/.