The ongoing COVID-19 (also known as coronavirus) pandemic is creating challenges for organizations and individuals around the world. Most organizations have implemented remote working for their employees where possible. This transition changes how employees access data and communicate with colleagues and customers. That change creates an opportunity for threat actors who seek to exploit the situation for financial gain or intelligence gathering.

Secureworks® Counter Threat Unit™ (CTU) researchers are tracking multiple coronavirus-themed campaigns across customer telemetry and third-party reporting. As of this publication, there has not been a noticeable increase in detections across customers’ managed security controls since the beginning of 2020. However, there is clear evidence of well-established cybercriminal and government-sponsored threat actors leveraging general interest in COVID-19 to entice victims to open malicious links and attachments. CTU™ researchers have observed government-sponsored hackers weaponizing coronavirus-themed Office documents and sophisticated criminal operators targeting critical infrastructure and organizations in areas hit hard by the pandemic.

The international response to the pandemic will be the subject of intelligence focus for some countries, as they seek to understand what other countries and international organizations are doing, saying, and thinking beyond public statements. This focus has likely shifted targeting requirements for some intelligence agencies and their associated cyberespionage operations. For example, Iranian government-sponsored threat actors reportedly attempted to infiltrate the World Health Organization.

Meanwhile, traditional cyberespionage activity continues. There have been many examples of government-sponsored actors incorporating the COVID-19 situation into their standard targeting operations:

- Word documents using Taiwanese, Vietnamese, and English language coronavirus-themed lures in February and March have been attributed to BRONZE PRESIDENT (also known as Mustang Panda).

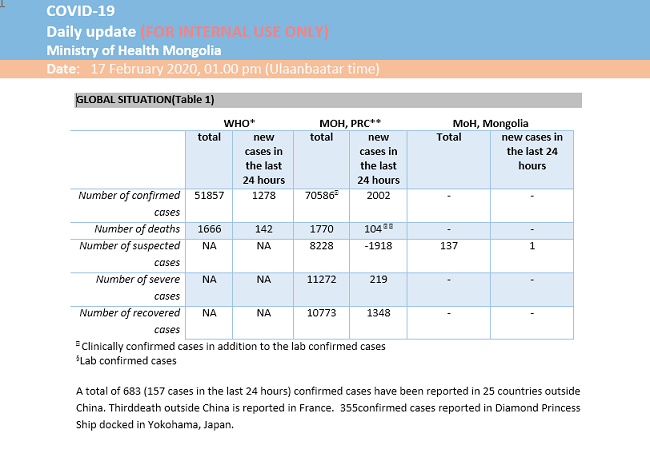

- CTU researchers analyzed a malicious RTF document in February linked to threat actors suspected to be based in China. This purported update from the Mongolian Ministry of Health on the global COVID-19 situation (see Figure 1) dropped the PoisonIvy remote access trojan.

Figure 1. Malicious RTF document linked to suspected China-based threat actors. (Source: Secureworks) - The Pakistan-based COPPER FIELDSTONE threat group (also known as APT36) reportedly leveraged the coronavirus pandemic in a lure document supposedly from the government of India. The document dropped the threat group’s signature CrimsonRAT malware.

- In March, a file named “COVID-19 and North Korea.docx” was uploaded to the VirusTotal analysis service and was observed contacting a command and control (C2) domain associated with the North Korean NICKEL KIMBALL threat group (also known as Kimsuky).

- On April 3, researchers noted a COVID-themed malicious document (maldoc) that used a C2 domain linked to the TILDEN threat group (also known as Gamaredon). CTU researchers assess that TILDEN may be associated with Russian intelligence services.

Well-resourced cyberespionage groups can rapidly adapt their targeting to take advantage of emerging opportunities. Due to public interest in COVID-19, spearphishing attacks using this theme are more likely to be successful. It is highly likely that threat groups will also explore their targets’ increased attack surface as employees transition to working from home and the uptake in remote access and conferencing solutions continues.

Although hostile foreign intelligence services might not factor into every organization’s threat model, all organizations should consider risks posed by financially motivated cybercriminals. Those groups have also quickly pivoted to exploit the COVID-19 pandemic:

- The Italian government implemented quarantines in Lombardy and 14 other affected provinces on March 8 and then extended the lockdown nationwide on March 10 in response to rising numbers of infections. On March 2 and 3, when it was clear that Italy was facing a challenge in containing the spread of the disease, several high-volume Italian-language spam campaigns began distributing the TrickBot malware. On March 13, CTU researchers observed Italian banks being added to TrickBot web inject configurations. This timing could be a coincidence, or GOLD BLACKBURN could have recognized that social isolation might result in an increased dependency on online banking.

- In late February, REvil ransom notes containing the names of Italian manufacturing companies began to appear. It is possible that one or more REvil affiliates are deliberately targeting organizations that might be more susceptible to extortion because they are already facing an extremely challenging economic outlook.

- A legitimate coronavirus tracking map was weaponized with the AZORult information-stealing malware and sold on underground forums.

- The LokiBot information stealer has been dropped via a maldoc that uses a World Health Organization theme.

- An email sent in March claiming to provide tips on how to avoid COVID-19 scams delivered the Gozi ISFB (also known as Ursnif) banking trojan.

- Threat actors have purportedly attempted to brute force Linksys routers so they could modify DNS records to redirect network traffic to a coronavirus-themed malicious website delivering the Oski stealer malware.

- The corona live 1.1 app claims to track the coronavirus but actually delivers the commercially available SpyMax spyware in a campaign targeting Libyans.

The fundamental business model and revenue generation of these sophisticated criminal groups does not really change as a result of the global pandemic. But fear, uncertainty, and a thirst for information about the current situation increases the number of potential victims and the likelihood of successful attacks.

Some threat actors have granted the healthcare sector a partial reprieve from this activity. GOLD VILLAGE, which operates the Maze ransomware, stated on March 18 that it would no longer target healthcare. However, the threat actors subsequently advertised compromised healthcare organizations. Since March 24, the GOLD TAHOE threat group, which operates the Clop ransomware, has included a message on its public name-and-shame website that the group will not target healthcare. It is perhaps too early to determine if there is some honor among thieves.

The activity receiving the most public attention includes spoofed domains, disruptive acts targeting remote conferencing services, and other scams. Unlike some of the threats discussed earlier in this blog post, the challenge for security teams in these incidents is identifying the malicious activity amid the noise.

- Over 90,000 coronavirus-themed domains that included terms such as covid, corona, chineseflu, and wuhan were created between January 1 and April 1. The vast majority of these domains will not be linked to active cybercrime or targeted activity, but some undoubtedly will be.

- Threat actors are taking advantage of increased teleconferencing use, spoofing legitimate applications to deliver malware and creating malicious domains imitating platforms such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Google Hangouts.

- The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) warned of teleconferencing services being hijacked (also known as Zoom-bombing), noting incidents in two U.S. schools. A significant proportion of activity targeting remote conferencing services will be opportunistic and intended to cause minor disruption. However, sophisticated threat actors will try to find and exploit vulnerabilities or weaknesses in those platforms.

- Threat actors created sextortion emails that threaten to infect the victim’s family members with coronavirus if a payment of $4,000 USD is not received. While these threats cannot be fulfilled, they may be convincing enough to scare victims.

- The FBI identified an SMS phishing (smishing) campaign that appeared to be a message from consumer products wholesaler Costco. The message offered money for completing a survey, but the survey is hosted on a malicious website.

- Alleged government-funding opportunities have been advertised through Facebook Messenger. These scams instruct the recipient to pay $20 USD for shipping of a “grant” check that never arrives.

CTU researchers recommend that organizations apply the following mitigations for coronavirus-themed threats. Many of these security practices protect organizations against other threats as well.

- Train employees to recognize and report phishing and other scams. These attempts could leverage via email, phone, social media, SMS (text), or other messaging applications.

- Conduct regular vulnerability scans, particularly of Internet-facing infrastructure. Ensure that devices and applications are centrally managed, are installed from known-good media, and are regularly patched.

- Use multi-factor authentication where possible. Requiring additional authentication elements makes it difficult for threat actors to gain access using stolen user credentials.

- Implement endpoint and network monitoring controls to detect malicious activity. Focus on detecting and investigating unusual activity from weaponized files, such as launching PowerShell, WMI, WScript, or unusual network communications.

- Where possible, require users to connect through corporate resources such as virtual private networks (VPNs) and DNS servers to access the Internet. This approach provides additional monitoring opportunities if user endpoints are compromised.

- Consider the organization’s security requirements when selecting a remote conferencing tool and vendor to ensure that the tool allows for an appropriate level of protection for conversations and data.

- Issue guidance to employees regarding proper use of remote conferencing services. Use passcodes or other authentication features, and do not publicly disclose meeting IDs where possible.

- Review incident response plans to ensure that remain appropriate for the modified work environment. Consider how to test those plans without adding unnecessary stress to the organization.

- Select a full-service threat intelligence provider, or several complementary ones, that offers coverage to support the organization’s threat model and that reduces the potential of internal security teams spending their time chasing false leads.

Secureworks has been acquired by Sophos. To view all new blogs, including those on threat intelligence from the Counter Threat Unit, visit: https://news.sophos.com/en-us/.